Mahli Mechenbier is a senior lecturer at Kent State University at Geauga/Twinsburg, in the English Department, where she has taught since 2006. She was born in Vietnam during the Vietnam War and was one of more than 3,000 children who were evacuated from the country through “Operation: Babylift.”

“Operation: Babylift” was a humanitarian mission by the U.S. Government to airlift orphans out of Vietnam when Saigon came under attack in 1975. Children were relocated and adopted by families in the United States, Australia and other allied countries.

Mechenbier, in person, and her father, via Zoom, met with Kent State Today to discuss their upcoming presentation, scheduled for 1 p.m. on May 3 in the Kiva on the Kent Campus as part of Kent State’s annual commemoration of May 4, 1970. “Operation: Babylift: A 50-Year Retrospective and Personal History” will explore the lasting impact of the Vietnam War, connecting the conflict’s humanitarian and historical consequences to Kent State’s Legacy. Tickets are available for download through .

Before They Met

Mechenbier was found by the side of the road near a public market by a nun outside of Saigon when she was an infant. She says the placement was most likely intentional; someone had placed her there with the intent that she be found as people walked to town that morning.

Her father, Retired U.S. Air Force Maj. Gen. Ed Mechenbier, was captured along with his “backseater” when their F-4C fighter jet malfunctioned after a bombing run north of Hanoi. After he and his co-pilot ejected, as they were parachuting to the ground, he saw “Six million people down there, no exaggeration, six million and they’re all shooting at me.” Mechenbier quickly discarded his .38 “survival weapon” pistol. He landed on a roof, rolled and was completely wrapped in his parachute when the Vietnamese soldiers captured him.

He was a prisoner of war for nearly six years (“2,076 days,” he said. “But who’s counting?”) from 1967-1973. He and other American prisoners lived in terrible conditions, enduring torture, starvation and isolation. In a consolidation of prisoners by the North Vietnamese, he was moved in 1970 to the Hỏa Lò Prison – which famously came to be called “The Hanoi Hilton” – and was liberated along with the rest of the prisoners in 1973. He was then assigned to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.

‘Something Good Did Come Out of This’

The children from “Operation: Babylift” arrived in major transportation hubs in California like Los Angeles and San Francisco and were sent to locations across the country for adoption. The child that would be adopted by the Mechenbier family was sent to the Mount St. Joseph Infant and Maternity Home in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Mechenbier and his wife came to adopt through their church in Fairborn, Ohio. A priest, along with a nun who had been in Saigon, asked if they would be interested in adopting a child. The Mechenbiers quickly answered “Yes.”

When asked if he was concerned that adopting a child from Vietnam would trigger unpleasant memories of his time as a captive, Mechenbier said that he didn’t think that at all. “All I saw was a beautiful baby girl,” he said.

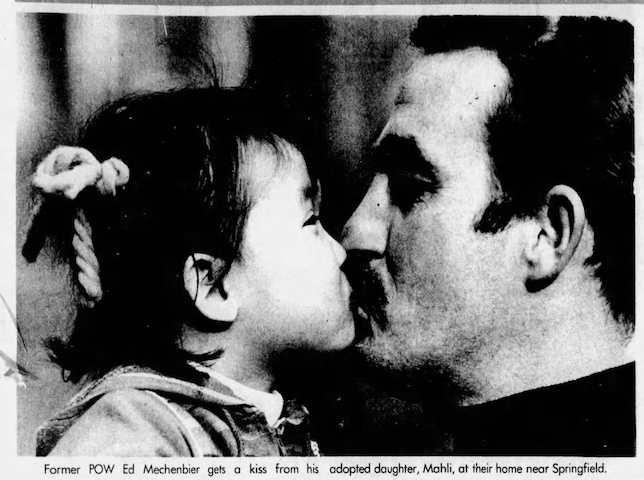

He said he sees his experiences in Vietnam as “a void” – except for his daughter. In a 1978 newspaper interview, Mechenbier said, “I can look at her and say ‘Well, something good did come out of the whole experience.’”

Mechenbier speculated that this sentiment was likely shared by the politicians who conceived “Operation: Babylift.” “I think a lot of the upper-echelon federal politicians were thinking ‘We need something good to come out of this.’”

The Lasting Impact of Being Raised by a POW Parent

In speaking with father and daughter together, their strong bond is evident as is the love between them and the unique sense of humor they share.

The conditions Mechenbier suffered while in captivity had lasting, negative impacts on his health. They also gave him a profound appreciation and gratitude for his life after captivity. “The takeaway from all this is that I learned to appreciate everything in life, even the little things.”

“Things like the hot water’s on the left, cold water’s on the right. When was the last time you were somewhere that it wasn’t?” he said. “You take it for granted. Where’s the light switch? Right there inside the door about that high where it’s conveniently located. So, it’s not like I’m wrapped up in an American flag saying ‘Oh, life is wonderful,’ No, I just put it in my mind that I lived, and 58,000 other guys didn’t. Be grateful for what you have. It’s not a model or an emotional thing that wraps up my entire life, but I just have that subtle everyday thought: thank you.”

Mahli Mechenbier acknowledges that her father’s experiences and her closeness with her father have made her more resilient and shaped the way she approaches life.

“People who know me are aware that I will eat anything, she said. And part of that is because of Dad. When you’re being raised by him, (you say) ‘I don’t like my cereal,’ (and he says) ‘Does it have bugs in it?’ ‘No.’ ‘Well then you can eat that.’” “Dad always reminds me of a quote from one of his POW colleagues, ‘If you wake up and the doorknob turns on your side of the door, it is a good day.’”

Her father’s influence has also come into her classroom in the way Mechenbier teaches and interacts with her students. When her students stress about getting a lower grade on a test or an assignment, she pragmatically reminds them that “it’s not the end of the world; you’ll improve on the next assignment.”

‘All of Those Things Make You Who You Are’

While Mechenbier has no memory of Vietnam or her birth parents, she recognizes the importance of remembering where you came from, which, in her case, is the Mechenbier family.

After learning her story, some of her students have asked her if she has ever searched for her birth parents.

“I respect my family,” she said. “I have a great family. I think I turned out fine. So, if you were to meet my brother, we sound alike; we have the same mannerisms. Dad and I have the same alertness and humor.”

She told her students, “We all have an origin story. We all come from somewhere and we have to find within that origin story sadness, happiness, joy, truth, reality. And if we don’t acknowledge and accept who we are, and if we don’t acknowledge and accept that origin story, we’re not being true to ourselves.”

“So even though you may have had it really rough as a child, or have faced challenges as an adult, or if you’ve had the extreme experience of being a POW, all of those things make you who you are and impact how you perceive and respond to situations for the rest of your life.”

And There’s So Much More

Anyone who wants to learn more about both Mechenbiers, father and daughter, can hear more of their “origin stories” live at their presentations at 1p.m. on May 3.